I fly with students as a safety pilot in aerobatic competitions on a fairly regular basis. Flying as safety pilot provides a unique experience because I am watching somebody compete, somebody I have probably trained and know their flying abilities well. Their actual performance on the “big day” is often far inferior to their proven capability. I have studied this difference carefully and have worked out over a period time the reasons for the difference in performance.

This blog will describe how to fly in the box and present your sequence optimally. It will also explain how to minimise the effects of stress.

Positioning

The judges need to clearly see the shape of each figure and be able to easily assess your accuracy. This demands that you fly in the optimal position in the box. Doing so for each figure will allow you to earn the best possible marks for each figure but also the best possible score for positioning, which is multiplied by a K factor in the same manner as each figure. Interestingly the positioning k factor, changes according to the level you are competing at, but is higher than for many figures and is therefore really important.

The Box

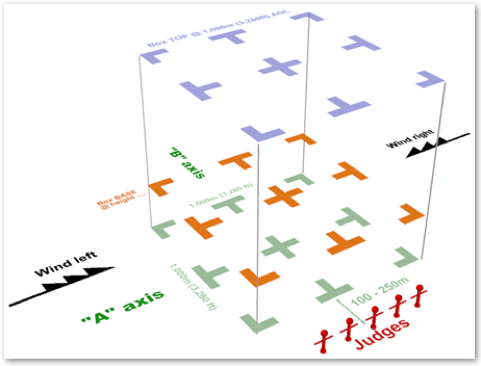

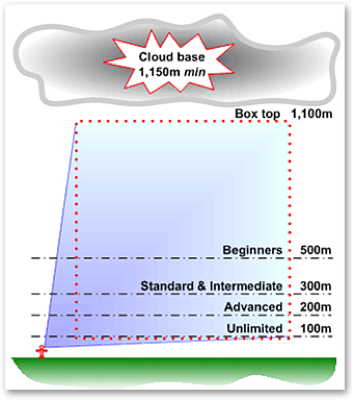

(above pictures with kind permission of British Aerobatic Association)

The box is a 1 km cube of air 100 – 250 metres in front of the judges (see diagram above). The axis from left to right as viewed from the judges is called the A axis the fore and aft is called the B axis. At the beginning of each day, the chief judge will nominate a competition wind that is along the A axis and will be the direction that most closely corelates to the actual wind. Each sequence defines the direction of each figure in terms of the A axis and this is mandatory, I.e. if the first figure is defined as starting into wind, if you fly it downwind, you will score zero. B axis figures may be flown either towards or away from the judges.

Different classes have different base heights. Club, previously known as Beginners, have a base height of 1,500 ft (500m) Sports, previously known as Standard have a base height of 1,000 ft (300m) as do Intermediate. Advanced is 650 ft (200m) and Unlimited is 100m. If the judges believe you are flying below these base heights you will incur a very significant point penalty. The Top of the box is notionally 1,100m but this is not enforced at the lower classes because it is more important to have the reassurance of extra height if the experience level of the pilot makes this necessary.

If a competitor flies a loop very close and high then the judges’ line of sight will obscure the shape and make it difficult to judge. Similarly, if the competitor flies at the back of the box the aircraft is likely to be too far away for the judges to accurately judge the sequence. In both these circumstances the judge is obliged to reduce the score given appropriately.

Generally speaking the aircraft needs to be between 400m and 750m from the judges to be judged well. The sequence should also be balanced and centered on the judges and each figure ideally positioned inside the box. At the lower levels being balanced left and right is more important than being precisely inside the box, i.e. you are likely to lose more points squashing the sequence in than flying 50m outside the left and right-hand side of the box.

This all sounds good but is rather more difficult than it initially appears because parallax plays an important part and the nose and wings obscure vision. Generally speaking the lower you are, the nearer the front of the box you should be. I have already explained the minimum heights and the penalty for going low. However, it is much easier to position correctly if you fly towards the bottom of the box and more difficult the higher you go. At Club and Sports levels, you can of course take a free brake at any stage and reposition but Intermediate and above this attracts a penalty (smaller than going low).

Wind Correction

Having described the aim of positioning it is important to compensate for the effect of wind. The wind will be blowing you down the box but probably also either towards or away from the judges. Your challenge is to compensate for the wind without getting downgrades for not flying on axis. Each figure is marked out of 10 and you lose 1 point for each 5 degrees of error! To make things worse, the wind changes direction and speed at different heights!

Wind correction needs to be applied both on the A and B axis. A is reasonably straight forward, all that is necessary is to extend into wind between figures and reduce the time between figures downwind. This should be balanced and rhythmic. If for example, you rush the first few figures and then fly 15 seconds into wind to compensate, you will be marked down. This necessitates looking at the judges between each figure and during each figure so that you can measure how much correction is required. The B axis is a little more challenging because instead of 1,000 metres performance zone you have in reality just 400 metres. You are required to stay on axis, so any into wind correction on or off judge needs to be so small as to be invisible. In real terms judges cannot see a 1 or perhaps 2-degree deviation from heading and this should always be applied into wind so that cumulatively a reasonable correction is made. Remember that if, for example, you are going to fly a loop, this 1 degree of error should be removed before pulling up into the loop otherwise not only will you lose marks but when you are upside down, the wind correction will make your position worse. This is even more obvious if flying a Half-Cuban. This is unlikely to be enough so needs to be applied alongside other wind mitigation measures:

If the above is not sufficient then the following options may be considered:

If you make all corrections in the correct sense and exercise subtlety, you will generally succeed but of course practice is essential. This all presumes you know what the wind is actually doing in the box which is quite often not the case.

Understanding the wind

Looking at the windsock prior to planning your sortie is essential. A good general rule is that the 2,000 ft wind will be double the windsock wind speed and veered 30 degrees. Watching other competitors may be useful although you do not know what wind correction measures they are taking therefore it is difficult to read the wind from what you can see.

The best method is to measure the wind while you climb in the box and then continue to judge your movement relative to the wind as your sequence progresses.

Measuring the wind in the box.

It is quite difficult to measure the change in groundspeed associated with wind but it is reasonably easy to see how much you are being blown left to right. It therefore makes sense, prior to starting your sequence to climb in the box in a square circuit so that you can see the left to right drift on each side of the square and also have practice flying along the A and B axis, picking reference points etc.

Putting figure 1 in the right place

Good positioning in the box is easiest if the first figure is started in the right place. If not then your piloting skill will be required not just to combat the wind but also to correct the positioning error of the first figure. There are 2 challenges in doing this, firstly is correctly calculating where this place should be and secondly, putting it there.

Looking at the windsock is going to give you a good idea where you should start and assessing the wind while climbing in the box will allow this to be refined. You are also allowed warm up figures. These vary according to the class you are flying, but at a minimum these are 2 half rolls (Sports and Club). Having calculated where you want to start, you can use the warm up figures to practice doing so. This is important because it is normally impossible to see beneath you or in front so you need to use reference points to the side and towards the horizon.

Wing Rocks

These are not judged but are the first bit of your flying that the judges will see. If they are feeble then the judges, being human are likely to anticipate your aerobatics to be similar and subconsciously look less favourably at your flying. Crucially wing rocks should be used to see the judges and ensure you put figure 1 in exactly the desired position. To look good make them 90 degrees of bank and hold that position for a few seconds without losing heading or height. This requires practice. The sequence starts after the aircraft is level following the 3rdwing rock. You will therefore be penalised if you do 3 wing rocks and then dive or climb for speed. If you do the third wing rock after diving for speed you will lose energy. Therefore, it is best to do the 3rdwing rock in the dive or if the 1stfigure is a low speed figure, in the climb.

Stress

It is remarkable how much the stress of the competition degrades most student’s performance in the box. Understanding this and developing a system to mitigate this is crucial to winning. It is probably not an exaggeration to say that it is not the best pilot who wins a competition but the pilot who is best able to cope with the additional stress or excitement.

Stress caused by the competition

This is natural and experience will greatly help. However, having a carefully rehearsed plan from take-off to landing will help a lot. Having fully prepared and anticipated various contingencies will reduce the pressure a lot.

It reduces stress a lot if you can be free of distractions. Wives, girl-friends, colleagues etc. all add to the general pressure of the occasion. It is best to discourage them coming although home politics might be a factor. Competitions are an occasion that bring together lots of like-minded friends. Stories are exchanged and experiences shared. It is ideal if at a fairly early stage you can break away from the pack and find a quiet corner to focus on your pre-flight preparation. Watch others fly the sequence, see what the wind is doing, work out where to put the first figure. After flying the known sequence, get the unknown sequence and learn it. Work out what the low point is and work backwards so that you know what height you should start at. You then need to calculate where the first figure should be placed. Work with a model so you know which direction you need to turn to ensure you fly on the A axis in the correct direction. Mark the vertical rolls on your sequence with opposite or same as appropriate.

Now you need to really learn every aspect of the sequence, where you are going to look etc. It is almost impossible to walk through the whole sequence without interruption, so break it down into two halves with a figure of overlap. Then do the “dirt dance”, once you can do this many times without fault, write the sequence out on paper from memory several times, then fly it with a model m any times. Then back to the dirt dance but this time walk through at extreme speed until you can complete consistently without error.

Stress caused by G

When pulling G, blood flow reduces to the head. Blood carries oxygen which is essential for thinking. If the brain is denied sufficient blood oxygen then you will lose consciousness, this is easy to understand but perhaps more importantly and less obvious is that your ability to think is reduced proportionally to the reduction of oxygen serving the brain. It is therefore very important to stress your stomach muscles and push the blood into your head before and during all positive g maneouvres. In a recent competition I saw 4 potential winners throw away any chance of victory because they were not able to think sufficiently clearly after a big pull. A big brain fade will result in the wrong figure being flown, but even a minor brain fade will prove expensive because competition aerobatics demands you think clearly during your sequence so that you can optimise the positioning of each figure for presentation and for aircraft performance.

Of course reading this is easy, the real answer is structured training and critique with the British Aerobatic Academy contact Adrian.Willis@BritishAerobaticAcademy.com+44(0)771 2864413 to book. Get ahead of the competition before the new season starts!